Exhibition Structure

I. A Cultural Symbol of Earthquake Recovery

Architect Tadao Ando, born in Osaka in 1941, considers Kobe his second hometown. He spent much of his formative apprenticeship period in the city before establishing his own architectural office. Also, his interactions with members of the Gutai Art Association and other artists with ties to Hyogo Prefecture had a profound influence on his approach to architecture.

The Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, which struck on January 17, 1995, was a deeply shocking event for Ando. Faced with the sight of cityscapes near and dear to him reduced to rubble, he felt an indescribable sense of loss and indignation at the helplessness of cities and buildings, which should have saved people’s lives and guaranteed their safety.

The Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art, designed by Tadao Ando Architect & Associates, opened in April 2002 as a symbol of cultural recovery from the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake. Ando has carried out many other post-disaster reconstruction projects centered on the theme of coexistence between architecture, nature, and culture, including the community development of HAT Kobe, which encompasses Nagisa Park next to the museum, and Awaji Yumebutai. Meanwhile, he has pursued initiatives outside the scope of architecture, actively engaging with society through efforts such as launching the Hyogo Green Network, a community-driven tree-planting movement aimed at fostering emotional recovery, and establishing a scholarship fund for children orphaned by the disaster.

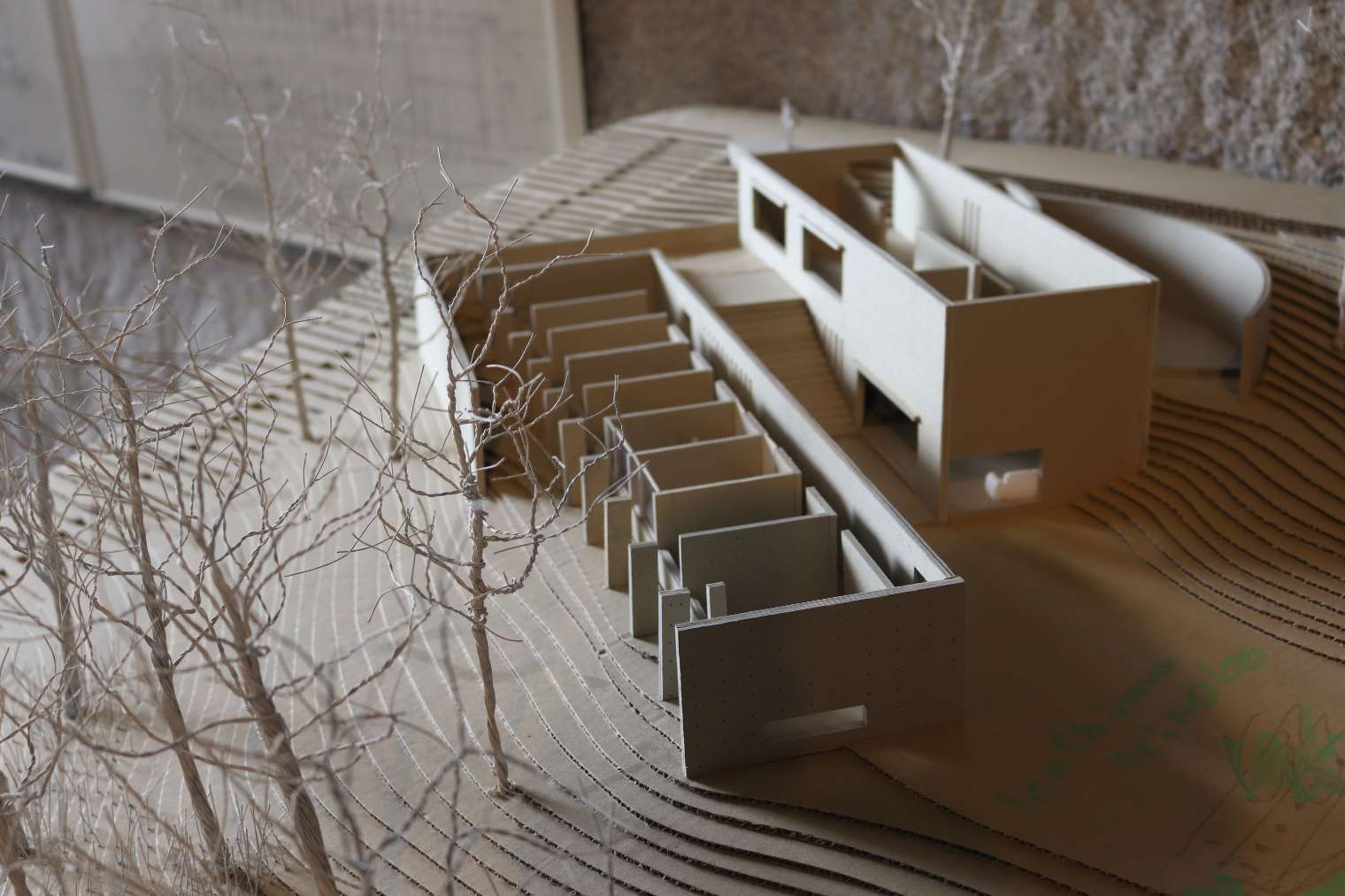

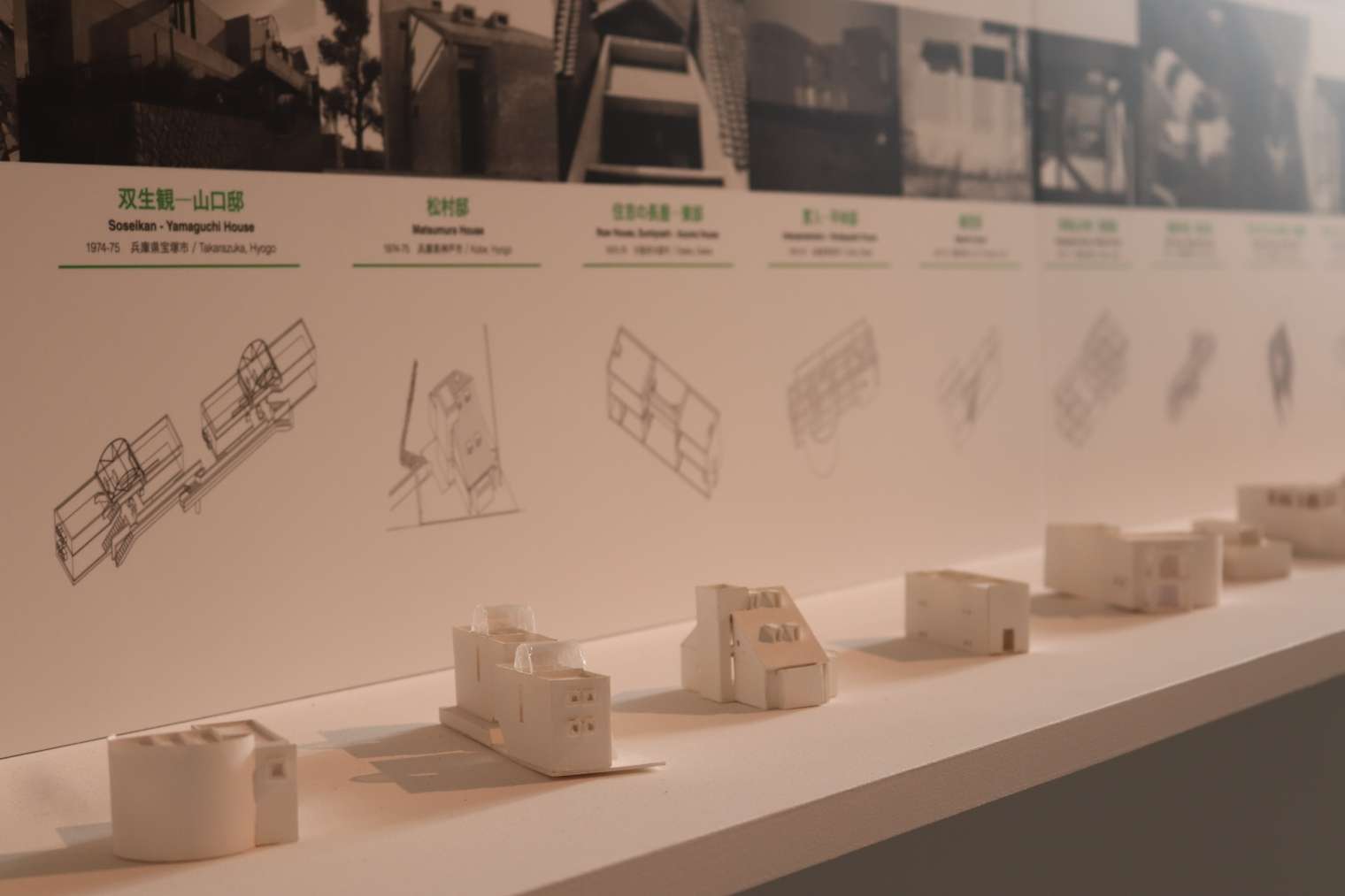

II. The House as the Origin of Architecture

In 1969, at the age of 28, Tadao Ando established his own architectural office in Osaka. Ten years later, Row House in Sumiyoshi, widely seen as his de facto debut, became the first single residence to receive the Architectural Institute of Japan Prize. The work reflects Ando’s keen sensitivity to buildings’ surroundings and refined sense of proportion through a rigorously composed structure of planar exposed concrete, finished with extraordinary precision. Light pours from above into the tightly enclosed space, producing an atmosphere that is both serene and dramatic. Taken together, these elements explain the enduring appeal of Ando’s architecture across cultures and generations.

After graduating from high school, Ando gave up on university due to financial constraints and other factors, instead studying independently while gaining hands-on experience at building sites. His stunning entrance into the architectural field caused a major stir. At the time, some architects were distancing themselves from the rationalism and functionalism of modern architecture by referencing historical styles out of context while embracing bold imagery and decorative elements. By contrast, Ando reduced his practice to the fundamental relationship between a human being and a building, reexamining its essence and offering a powerful counterpoint to prevailing trends. While drawing on modernist principles, he developed a distinctive philosophy that pursues the physical experience of space, the character of place, and the spiritual dimensions of architecture.

Here, in line with Ando’s belief that “the house is the origin of architecture,” we present his early works, including Atelier in Oyodo (the first residence he designed, later renovated multiple times to serve as his own office) and Row House in Sumiyoshi. Also featured are his three renowned churches, including Church of the Light, which represents a purely distilled exploration of space defined by light.

III. Nurturing the Future

Reading and traveling both require space, time, and freedom—the freedom to think for oneself and act based on one’s own will. Tadao Ando understands the importance of this through personal experience. His mentality is strongly reflected in many of the social and educational projects he has undertaken, beginning with his first public building, Children’s Museum, Hyogo.

At 18, Ando came across the complete works of Le Corbusier in a secondhand bookstore and was fascinated. Whenever he had a spare moment, he would pore over the pages and trace the drawings again and again. In 1965, a year after Japan lifted its ban on overseas travel for tourism, he set off alone to see the world, using money he had saved from part-time jobs at various architectural offices. During his travels, he learned a great deal first-hand, spending his days walking, sketching, taking photographs, and reading.

In a message for Kobe Children’s Book Forest, Ando reflected on how, as a child, he had little opportunity to read and only came to understand the joy and importance of books later in life. He expressed regret at not having been exposed to picture books and literature from a younger age. These sentiments led to the launch of the Children’s Book Forest Project, which has since expanded both in Japan and overseas. Meanwhile, as another initiative aimed at creating spaces where people can encounter not only literature but the arts more broadly, this section also introduces the many Naoshima Projects carried out in collaboration with the Fukutake Foundation. These carry on the vision of the founding president of Fukutake Publishing (now Benesse Holdings), who aspired to create places on the islands of the Seto Inland Sea where children from around the world could gather.

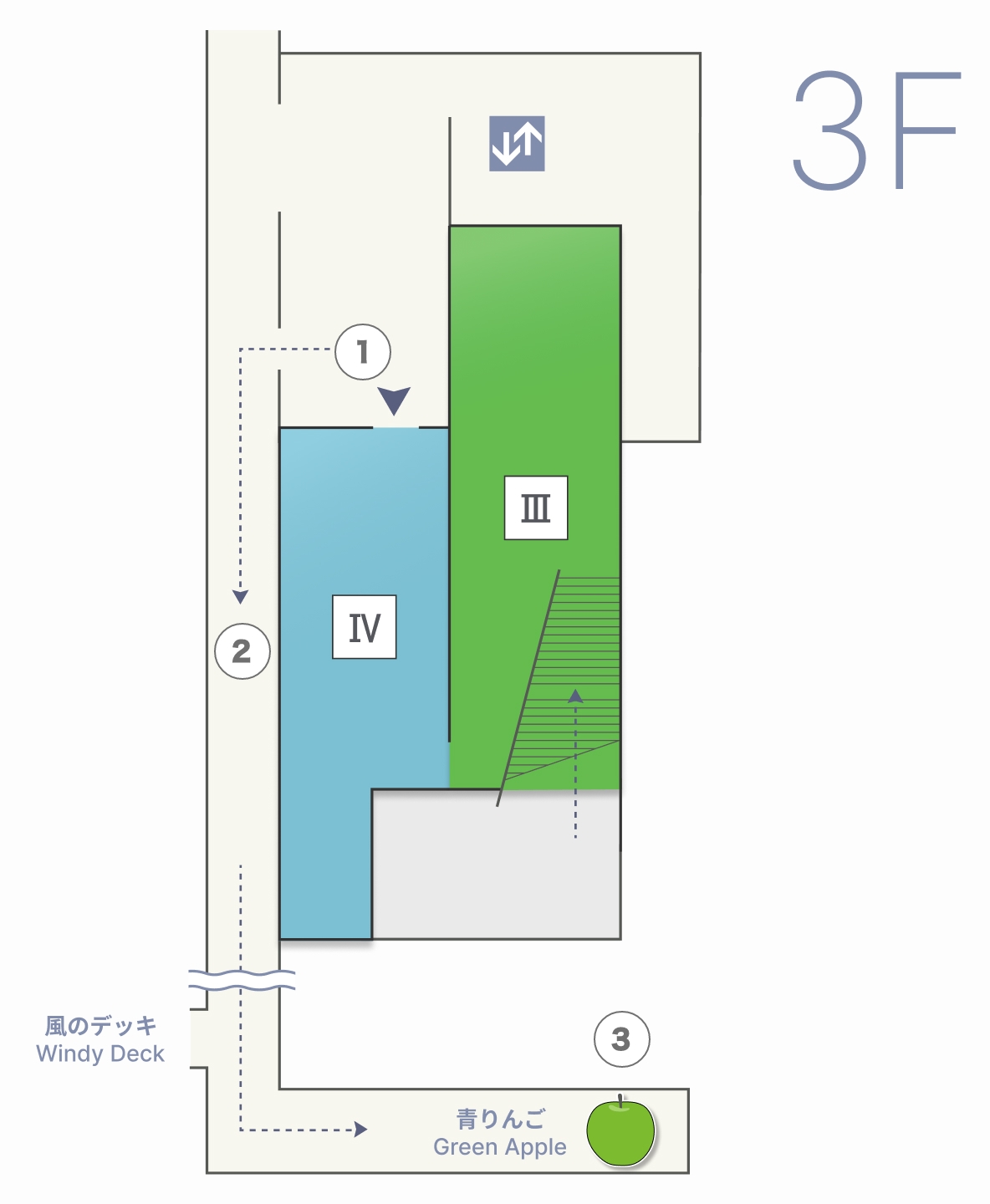

IV. Houses for the Arts

The Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art, which opened in 2002, and the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth were both realized through international design competitions, in which Tadao Ando’s proposals were selected from among numerous submissions. In these projects, Ando brought to life a double-membrane structure he had long envisioned, with concrete volumes wrapped in glass walls. Exposed concrete is a trademark synonymous with his work, and this concept allowed him to build enclosed exhibition spaces with this material while also creating semi-outdoor zones reminiscent of verandas. The results embody his vision of a contemporary 21st-century museum, rooted in its local context, with a seamlessly integrated interior and exterior.

In 1999, while both the Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art and the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth were under construction, Ando wrote the following in a magazine article:

I have a dream. I envision a museum network that connects the various museums I’ve had the opportunity to be involved with, where the buildings act as hubs. (…) The Seto Inland Sea cultural network would link with other cultural networks across Asia and the world, forming a vast web that interconnects the globe with invisible threads. In this environment, where multiple cultures intersect and overlap, children would gain a wide range of experiences. I believe true affluence lies in how much freedom one can find, and how fully one can shape one’s own way of living, through such diverse experiences.

Here, we present the many museums Ando has designed around the world. From the Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art, which faces the Seto Inland Sea, we invite you to look out beyond Green Apple to the sea and the world beyond.

Green Apple

The “Green Apple” sculpture on the Sea Deck of our museum was donated by Tadao Ando Architect & Associates along with the Ando Gallery, which was added as an extension in 2019. Inspired by the poem Youth by the American poet Samuel Ullman (1840–1924), Ando created this work as an homage to its beautiful and powerful words. He placed it here overlooking the sea, with the belief that people, architecture, cities, and societies are at their best when they are still green and filled with a spirit of endeavor.

-

Photo by Nobutada Omote -

Photo by Nobutada Omote -

Photo by Masaki Tada

Access to Green Apple

① Exit the upper floor of Ando Gallery and turn left.

② Walk straight with Ando Gallery on your left.

③ At the end of the walkway, you’ll find the Green Apple on the Sea Deck to your left.